The gift of transcendence under my nose

Surrendering to the divine at a religious music festival

Over Memorial Day weekend, I spent seventeen hours in a massive Orlando hotel ballroom at the Sadhu Sanga kirtan festival, a yearly gathering organized by devotees of the International Society of Krishna Consciousness. For at least the past five years, I’ve been obsessively searching for kirtan rasa—the ecstatic emotional experience of chanting. With increasing success has come impatience with the hollowness of urban American life and status games.

There’s no thesis today. These are observations from the field about the nature of lived Hinduism in the diaspora and among non-native people who have taken up various paths of Hinduism. This is also a personal narrative about my childhood growing up in North Florida in the Hare Krishna community of Alachua, the largest of its kind in North America.

Growing up in the Alachua temple, I didn’t realize the preciousness of what I had in childhood. In the 90s, it was a mobile home among other mobile homes in which devotees of the movement were trying to rebuild after the many scandals that plagued the national organization in the 80s. These are devotees of the god Krishna, and they would describe their sect as monotheistic with its focus on Krishna at the exclusion of other gods.

A brief orientation to Hindu deities and sects

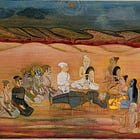

If you’re wondering about Krishna’s place in the pantheon, he’s the primary deity worshipped in the various Vaishnava sects. The term ‘vaishnava’ refers to followers of Vishnu, the preserver god of the Hindu pantheon. He is usually mentioned with Brahma, the creator, and Shiva, the destroyer, but Vishnu’s various manifestations are more widely worshipped in specific regions and families. While Hare Krishna devotees consider themselves monotheistic, the plurality of native-born Hindus recognize forms of Vishnu and Shiva (their importance depending on the ritual context, time of year, caste, and region).

It’s a little convoluted, like most Hinduism, but Krishna can sometimes be the source of Vishnu or an incarnation, depending on who you ask. But when people refer to Vaishnavas, they’re referring to devotees of Krishna and those who worship myriad other forms of Vishnu. These deities furthermore have different names in every temple, despite their being technically the same god, Krishna, Vishnu, or Shiva.

ISKCON was dismissed for much of its history as cult-adjacent. Diaspora Indians generally worship far differently from ISKCON devotees and didn’t attend much back then; they often take a more rationalist approach, drawing on Advaita Vedanta, which posits that an impersonal divine force, brahman, pervades creation. Unlike Krishna, who is seen as a personal god you can love, brahman is a formless, all-pervading essence—more like pure being itself. The mostly bourgeois PMC diaspora Hindus find this more palatable because it’s easier to assert it as the equal of Western Christian divinity in its rationalist valence.

When I was growing up, diaspora Hindus stood there rather than go with the irresistible impulse to dance when the tempo increased. Singers were inflected with a yearning for Krishna and his divine consort Radha.

The drums don’t ask—they compel. To ignore them is to deny yourself an emotional release so powerful it often ends in weeping. But at this festival, at least sixty percent of the room was diaspora Hindus and their children. The cosmic irony here is profound: the founder of ISKCON came to the West to induce his countrymen to rediscover their spiritual heritage. He succeeded in that mission and gave diaspora Hindus the gift of a personal relationship with god that can’t be found in mainstream Hindu temples.

A couple of Indian immigrants join a group of former hippies in Florida.

A group of former hippies who became ISKCON devotees were chasing their manifest destiny in rural north Florida, buying acreage in the late 80s. My parents had joined the movement independently in Chicago in the late 70s. My mother took refuge in Krishna consciousness (for it is not merely “Hinduism”) after getting divorced and leaving India. At the same time, my father was discovered as a gifted salesman of religion by a white ISKCON swami in India after he’d been kicked out of his home in a UP village. I realized at the festival the extent to which my temple community is famous among ISKCON devotees globally. Growing up, I found the whole thing boring and borderline oppressive, even as I always found the divine in kirtan as embodied devotion. I was often at war with myself.

I thought my childhood was uncool and proletarian, but I was sitting among future greatness in the form of a musical group begun by the son of family friends. The man at the center of the kirtan renaissance, Vishvambhar Sheth, evoked spiritual transcendence when he played at my house on New Year’s Eve 2003. We had a small group of devotees over, and that night is etched in my memory because of the depth of emotion. I didn’t understand then that what Sheth was stirring deeply within me with his music was a unique gift he would later give the world.

I had zero connection with bhakti over the past decade, but discovering Sheth’s group, the Mayapuris, brought me back. The trio of Sheth, Krishna Kishora Rico, and Bali Rico is in high demand at festivals and yoga studios globally, and they’re the top of their field. The Sadhu Sanga festival I just attended came from the Mayapuris’ efforts, which began in adolescence. But they understood that kirtan, when unrooted from devotion to Krishna, becomes hollow-a vaguely exotic aesthetic, like Western yoga.

Somehow, I had never actually seen the group perform together until this festival:

The Mayapuris perform at religiously unaffiliated kirtan festivals, but actual devotees can access deep emotions and longing that their music evokes that outsiders can’t. This is why spirituality divorced from actual divinity can’t go beyond a certain depth. It’s not unlike the untethering of Western postural yoga from the quest for union with the divine that is true yoga.

I didn’t know it then, but Alachua had the most multigenerational devotee families. I attended regular schools in Gainesville, the neighboring college town housing the University of Florida. In contrast, the other kids my age attended the religious school on the temple grounds. That school had many scandals and had to close, but enough of the kids I grew up with stayed in the movement anyway and are now raising children in it. In contrast, thousands left the movement in the 80s in the wake of several scandals among gurus.

I went to the Alachua temple for a holiday last year. I found that the Rico brothers of the Mayapuris and several of the men I’d seen lead kirtans on videos watched by millions were also leading the congregation's regular worship. I wish I still lived there just to go to the temple on Sundays. What was once a mobile home is now a temple bursting with devotees.

The festival I just attended with two thousand others is the fruit of my generation's refusal to turn away from devotion, at which I failed miserably. Not only is the community itself famous, but several of those kids in my cohort are now renowned on the global kirtan circuit (yes, that’s a thing), and Alachua is a sort of pilgrimage spot for people like me chasing kirtan. The spiritual irony mocks me.

Just as I didn’t grasp the worth of UF, I didn’t recognize the gift of bhakti I’d been given in childhood, because the imperatives of academic rationalism made it implicitly shameful to believe in a higher power. In my case, one was expected to maintain a scholarly distance from one’s subject of inquiry—Hinduism. I studied Hindu metaphysics, literature, aesthetics, and global praxis, but my deepening expertise was inverse to my depth of devotion. I ended grad school as a self-professed atheist.

A path out of modern malaise: the integration of eros as desire for the divine

My life turned around because of discipline, or the integration of logic and structure in my life, which had hitherto been ruled by emotion, and returning to bhakti, or yearning devotion for Krishna. It’s not just for a generic divinity but Krishna in particular. I had to bring together pure consciousness and turbulent emotion, but channel it beyond myself instead of succumbing to the desire for worldly fulfillment.

This meant my career ceased to define me, my desire for social approval dissipated, and I reduced my attachment to my youth and beauty. I had to channel the desire elsewhere. The metaphysical eros is the soul’s longing for beauty, truth, and divinity — this is roughly the ethos of bhakti: the soul’s devotional yearning for union with the divine. It requires surrender to a personal god, usually Krishna.

But this surrender is suspicious and usually resisted in a supremely individualistic society that views religion with increasing hostility. Regardless of this, the Alachua community continues to gain devotees, and kirtan festivals globally attract people who never considered themselves devotees of Krishna or any god; they’re looking for something modern life can’t give them.

To that end, I encourage you to undertake a spiritual quest. Some of you are such rationalists that you will probably scoff at the suggestion. My partner, for example, often remarks on his distaste for most religious traditions save for Buddhism. I anecdotally observe that a specific type of rationally inclined man who dislikes religion usually finds Buddhism at least mildly interesting.

Many of you shun all religion because of your bad experiences with Christianity, but I feel that you might be missing out on something by painting things with a broad brush. Suppose you respond that you’re spiritual but not religious. In that case, I’d ask what you think that distinction is and if you’re missing out on community by creating a bespoke spirituality unmoored from structure.

I’m asking myself the same thing; I’m not part of ISKCON officially, though I consider myself broadly Hindu. But now I’m wondering if I need to become completely part of something to deepen my surrender to something beyond myself.

In the meantime, here is a playlist of the music that makes me weep involuntarily. I promise something will stir in you, too.

Hit the subscribe button to get new posts in your inbox. If you’re a free subscriber, please consider upgrading to an annual subscription for far less than the other topical things you pay for. What you get from me are difficult and unpopular truths grounded in philosophy and metaphysics. You can signal that this work matters in a sea of writers who parrot institutionally approved narratives. At the same time, those people dominate the conversation—they’re in the right places. I’m not affiliated with social contexts that constrain what I say, and that’s why I appreciate my readers so damn much.

Interesting description of Krishna/Vishnu/Shiva and the various incarnations. I don't know a lot about Hinduism; what little I know comes from discussions with Indian friends and to be honest I find it somewhat baffling. It occurred to me while reading this, though, that a non-Christian might find the concept of the Trinity (three manifestations of a single entity) equally baffling. It also occurred to me that such baffling mysteries are the heart of any religion; these mysteries force you to embrace the unexplainable; to, in essence, abandon the rational with intent, as it were.

I agree that we all have a yearning for beauty, truth, and divinity. Those who reject that yearning seem to me to be the most unhappy people I know, while those who embrace it have a serenity about them that I admire.

It’s fascinating how you’ve been drawn to ethos while also immersing yourself deeply in Krishna. To me, they feel like a kind of yin and yang that brings a striking balance to your perspective. You mention that many of your pieces are serious, but I actually find your approach to ideas quite playful, which makes your voice refreshingly distinct. Whatever spirit you are surrendering yourself to, it’s clearly guiding you well.