How the knowledge class killed the humanities

The Death of the Ineffable Part 1

I’m back after a break, and in the space of a month, I was able to figure out where I’m going intellectually. Without the pressure of publishing, I zoomed out to see the trunk of my theory of modernity, in which this essay is a case study. To those new here, welcome. I have deep gratitude for your attention to structural issues amid shallow takes on current events. If you came here for a gender critique, I promise I’ll get back to it, but I’ve now realized that various gendered phenomena, like my essay on women’s society, are actually the result of more foundational problems in epistemology, to which I now turn my attention.

Introduction

The narrative about the humanities has mostly been one of lamenting its demise in mainstream liberal publications, under pressure from shrinking professional job opportunities and a low return on investment for the costs of a degree. However, the frame itself is flawed. No one seems to have stopped to consider where the professional class caused the demise of the ineffable under a regime of measurement and classification.

This isn’t just about the absurdity of demanding that an area of inquiry correspond to a specialized skill, or about how universities don’t actually understand how the labor market works. The humanities train a person in discernment and broaden one’s possibilities of being in the world. They expose you to the subjective, sublime, and the range of human sensibility.

The professional class killed beauty

The professional class’s power rests on its ability to order the world. Managerial capitalism emerged from the need to coordinate resources at scale, and AI is the capstone of this project: the attempt to optimize human life from birth to death. Order is necessary for flourishing, but the drive for endless growth pushed us to the extreme, until all the juice is squeezed out of the human experience. What is missing is the ineffable — what Hindu aesthetic theory calls rasa, the deep pleasure and nourishment that comes from emotional evocation in art and literature. Extrapolated beyond art, rasa is the human experience of beauty, mystery, and inner life itself. Our world feels hollow because there is no longer room for rasa.

Many in the professional class overlook the crucial tradeoff of asserting power through processes and measurements — the demise of everything that makes life beautiful. This is why much dance, music, writing, and art in general feel hollow. By forcing beauty into metrics, we squeezed the very essence of why art matters. What remains feels hollow because its ineffable substance has been evacuated.

A liberal education was, until the last half-century, considered essential as a means of achieving the good life. Understanding human nature and culture fosters the development of empathy, which is essential for identifying the right problem to solve. But more crucially, one is encouraged to learn new frameworks for understanding reality and to develop judgment.

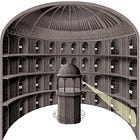

Credentialism as classificatory power

The humanities have died under the professional class’s regime of credentialism. The monopoly on expertise this class claims confers moral authority, the logical end of which is categorizing knowledge.

The need for specialization gave rise to this modern paradigm for knowledge production. Related to this, over the past four decades, credential requirements have increased for jobs that shouldn’t require them, as an easy sorting mechanism. The major became a secondary category for determining one’s qualifications for any job, even if it had no direct relation to the work performed. Credentialism is simply a sorting grid that reduces judgment to measurable proxies.

Using degrees as a proxy for ability elides the fact that no degree outside a handful in engineering is actually relevant to most jobs. Outside a few fields, the area of study rarely translates neatly to the required knowledge for a job, which raises the question of why we require a specific degree, or degrees at all.

The requirement for credentials for white-collar jobs is a contributing factor to the crisis in the humanities. In a country with a low median income, it is unjust to hoard the highest-paying jobs for those who can afford college and have studied a narrow range of subjects. The professional class has created a credential moat around itself by essentially making the degree the measure of merit for the white-collar workforce.

Credentialism is less about measuring ability than about preserving hierarchy. The proxy is the point. Classification creates the illusion of merit while serving as a gatekeeper to opportunities. The secondary effect is a civically uneducated citizenry.

The ineffable is a luxury good

The study of history, philosophy, and the arts was generally reserved for the wealthy until the mid-twentieth century, after World War II. When the humanities briefly expanded, they offered ordinary people access to cultivating discernment and taste. As credentialism tightened, that access was revoked. The ineffable was reclassified as elite luxury.

For elites, the ineffable is still permitted – philosophy, literature, and history confer status. For everyone else, it is forbidden. The classificatory regime not only enforces class boundaries but also allocates who is allowed to have contact with the ineffable. The mere middle and lower classes must choose a practical or vocational major to have a hope of passing the initial resume screen and getting an interview. Thus, we have not only credential discrimination, but humanities students also have to contend with a secondary prejudice against their areas of study.

If you dare to major in a humanities field, administrators claim your only path is academia or nonprofits, and recruiters looking for entry-level candidates similarly sort them based on the quantitative signaling of the major. This intellectually impoverishes non-elite students because they often eschew the humanities entirely. But even for elite students, the humanities degree is a luxury good, conferring social and moral capital rather than teaching how to cultivate discernment and build a good life.

Discernment is the key to success

Jobs like mine, which are equally about discernment as technical skills, routinely list a degree in computer science or its equivalent as a hard requirement. If I wanted to break into my field as a beginner, I’d be rejected. The demand for a quantitative field of study overlooks the significant need for reasoning in ambiguous situations, which is even more important for the highest-paying jobs.

I brought judgment, writing, and systems thinking to the table, precisely the ineffable skills the classificatory regime refuses to recognize. My own trajectory disproves the regime’s narrative. What initially appeared irrelevant on a résumé was, in fact, decisive in practice: history trained me in dialectical thinking and systems analysis, whereas technical majors often train in compliance and emphasize the empirical over the qualitative.

At the lowest levels, we look for specialized order takers. However, the most successful individuals reach new heights because they navigate uncertainty, synthesize information across domains, and think outside established frameworks. This is precisely what the humanities education is supposed to confer, but it has been hollowed out by optimization culture.

Irony of ironies: I am architecting and building AI chatbots that automate routine work typically done by the white-collar workforce, and I have become qualified to do so because I can synthesize and create systems. Anyone can learn to assemble an agent — the technical steps are trivial — but few have the discernment to decide what it should actually do, or what context it should draw upon. Data analysis itself is mostly intuitive judgment; yet, the credentialist story insists that you cannot do it without being an expert in SQL.

The system treats the measurable proxy as substance, while the substance of judgment is invisible because it’s immeasurable. The labor market only valued my ‘soft’ skills once I had acquired technical skills, which are still the primary proxy for my ability.

The technical world is awash in people who can write functions and click buttons, and impoverished in critical thinking and judgment.

The good life versus measurement

Liberal education’s original telos was to help one construct a good life. At the University of Florida, I witnessed the religion department nearly shut down during the financial crisis, an example of how ‘useless’ majors that nevertheless have intrinsic value are often the first to be cut. My study of history and religion, however, seeded my current intellectual project of cross-cultural philosophical synthesis.

The decline of liberal education not only hurts society but also ironically hinders the development of the decision-making skills that would lead individuals to success. Businesses need generalists and synthesizers far more than specialists outside a few fields; supposed jacks-of-all-trades are often more useful than masters of one.

Higher education tells the story that specialized credentials equal merit and ability, while the working world rewards the opposite. We are, therefore, producing a compliant and uncritical citizenry while also failing to produce workers with the necessary skills. Someone go tell the Democrats, defenders of higher education and opportunity.

Liberal education once aimed at the good life, not the good job. Its decline is not just an economic loss, but a civilizational poverty. Rasa, beauty, and discernment have disappeared from ordinary life.

Conclusion: returning to the ineffable

Where I’ve found discernment again is in retraining my desire toward higher-order goals. By this, I don’t just mean discipline, but the deeper question of what I long for in the first place. Modern life trains us to satisfy every appetite, and in doing so, it flattens desire itself. Discernment is the art of knowing which desires are worth fulfilling and when longing must be savored. This is what I gained from returning to devotional longing.

The classificatory regime makes this nearly impossible. By reducing value to what can be measured, optimized, or credentialed, we are blinded to anything beyond our senses. The result is a culture where beauty feels hollow, education is stripped of its purpose, and work rewards proxies over judgment.

Resisting the tyranny of classification requires recovering the capacity to dwell in what cannot be measured: in beauty, mystery, paradox, and longing. Liberal education once trained us in this posture, but even where it survives, it has been reclassified as a luxury good. We need a deliberate return to the ineffable, not as ornamental, but as the foundation of a flourishing life.

When I was in college, an older man asked me what I was majoring in. I replied “The Humanities.” He was quiet for a while then said, “You will never make a lot of money but you will have an interesting life.” He was right. I have had a very interesting life. Although I have not made a ton of money, I’ve made enough and have never struggled. If I could do it over, I would not change my major. Never

1. All systems that survive eventually are ruled over by sociopaths. That said, sociopaths do like attractive lovers to stock their beds.

2. At one time, engineering was seen as a low-prestige degree, a glorified mechanic.