Becoming Indian: performing identity in the American multicultural curry

What is Indian-ness and who gets to claim it?

i. I was never “Indian”

Before college, I wasn’t Indian, but a Vaishnav, one of Hinduism's three major sects. I didn’t have a racial identity paradigm from which to articulate my experience. From entering college until thirty-five, I thought of myself instead as Indian-American, until I realized that the identity is more about social performance for the professional managerial class rather than anything innate. One is not born, but instead becomes, Indian-American, and even more importantly for the PMC, South-Asian American.

And you should care, dear reader, because Americans of Indian descent (AIDs; also me) and Indian-origin Americans (IOAs) have quietly reshaped corporate America in our image, regardless of naturalization. This is an astounding feat for a population our size. And before someone calls me a nativist, I’m not making a judgment about it, but I'm going to parse it because you probably can’t see it.

Personalities reflect the traits best distributed in the population, and cultures produce personalities reflecting their normative characteristics. These two sub-groups, whom we consider “Indians,” are not the same species, though dominant identity discourse considers us the same, like reducing Indian regional diverse food to ‘curry’.1

I don’t come to this as an outsider; many might consider me very Indian to an uncool level, though I no longer do.

I’ve studied Hinduism and the Indian global bourgeoisie at length in graduate school, trained in classical Indian arts and aesthetics, and speak two Indian languages fluently enough to translate vernacular poetry. I imbibed Hindi and Gujarati before I spoke English. I’ve lived in India for extended periods, outside the padded walls of family visits. More importantly, I grew up a class and religious outsider within a professional-class diaspora community that seemed to have it all figured out. Then I climbed into that world myself — into a professional class now disproportionately of Hindu origin, whether or not we admit it. In this way, my view is both inside and outside at once.

I get the frustration of those raised in the US who never felt enough in any context. Despite my ‘qualifications’, I always felt like a freak because of how religious I was as a child among other diaspora Hindus. I also grew up with scarcity, unlike others in my town. Among the white girls, I was the conservative one with an overbearing mother. This is also for all of you, to validate that ‘being Indian’ doesn’t stand up to logical scrutiny for many of us. I don’t want to deny anyone the right to feel Indian if that makes you happy, but I would interrogate what you’re clinging to and why. And for Indian-origin immigrants, I get why you find us annoying, truly. We are very often irritating, and we sound like Americans to you. We can also frequently behave entitled.

The Indian diasporic professional fits in well with the rest of the white PMC. However, what everyone else sees as Indian also diverges, specifically regarding authority and hierarchy. India is a highly hierarchical society, not just in terms of caste and religion, but class maps onto those divisions. The American professional class, meanwhile, studiously denies hierarchies entirely in service of political ideology and class guilt. AIDs like me are caught in the middle of these personality tendencies — sometimes not deferential enough for IOAs but still coded as ‘brown’ by white people, despite basically acting ‘white’.2

My being an American woman of Indian descent makes the lens thicker. However, there’s always some way someone isn’t ‘Indian enough,’ meaning it’s more about ethos and behavior than any external cultural markers the rest of the world sees. This is how we socially police each other and compete. Identity is a performance for other Indians (of any kind) and the rest of the professional class, specifically elite white people.

ii. Deconstructing an ‘Indian’

The diasporic identity taxonomy requires explanation. Not only do we maintain caste consciousness (not in a good way) in the West, but we categorize each other according to perceived distance from the culture. We refer to each other as ‘desi’ internally, a North Indian shorthand for ‘nondescript South Asian’.

AIDs in college are often called the Indian grad students FOBs, or ‘fresh off the boat’, a catchall term in populations tracing roots to any part of Asia. FOB implies that one is insufficiently American, though the Indian immigrants we called FOBs would argue that AIDs like me are more concerned with ‘being Indian’ than actual Indians are. AIDs imagine India through cinema (not just Bollywood, by the way) as any consumer imagines another culture through media. Being an outsider in a foreign land creates a static impression of their home culture in our parents’ minds, which they pass onto their children. I had a far more conservative upbringing in Florida in the 90s than my urban Indian cousins.

My brother-in-law grew up in India and knows a lot more about Americana than my sister and I, because we weren’t allowed to watch most of what was on cable or listen to American music in the car.3 However, he and I both recall the Indian epic TV series Ramayan and Mahabharat, which tied the diaspora to the motherland in the pre-Internet era.

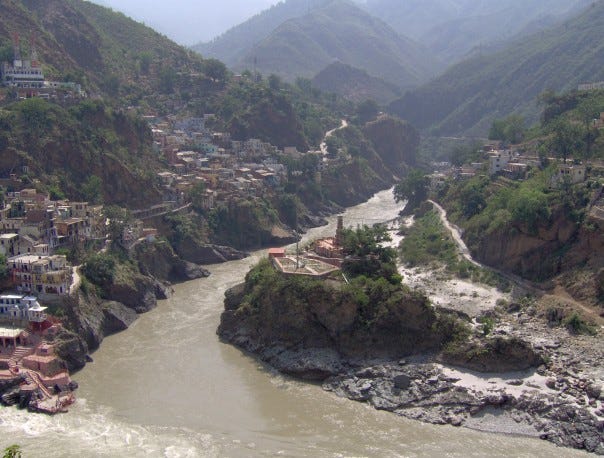

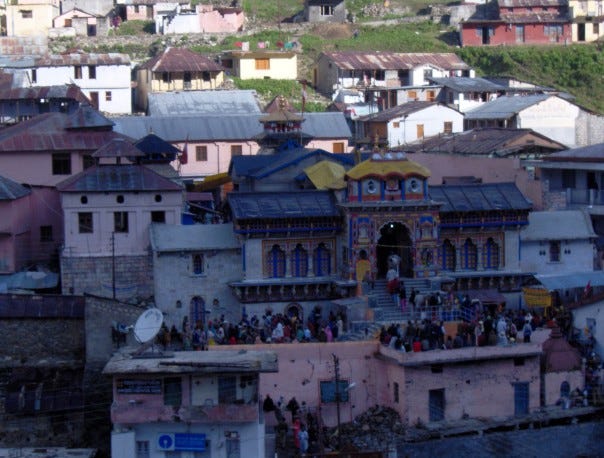

I’ve seen more of India than America because my mother took us on pan-India trips to various pilgrimage spots, which remain essential to the lived Hindu experience in India. I’ve visited far more holy places than the average desi of any type; being Hindu and devotional anchored me to India, the nation-state and spiritual nexus, more than mass culture. When I studied at the American Institute of Indian Studies in 2009 and 10, I was the translator and guide for all the (white) students. I also tracked down the bhang in Lucknow and Varanasi, which required linguistic skill and a certain amount of risk-taking.

This semantic slippage between ‘Hindu’ and ‘Indian’ obscures the former for several reasons. First, the national identity is conflated with being ‘Hindu’; they consider India a Hindu country even though it’s officially secular (another essay).

Second, all types of Indians uphold elite Western professional norms, in which religious identity must be obscured to project one’s credentialed enlightenment. Indians of any kind must maintain respectability in the eyes of the dominant elite.

Third, though one can be culturally Hindu, the non-practicing among us are likely more comfortable calling themselves Indian or of Indian origin because it’s more accurate.

Finally, AIDs have adopted Western leftist ideas and think identifying as Hindu obscures latent anti-Muslim sentiment, and carry Brahmin guilt instead of the class guilt they should have, much like elite white people should be more conscious of class but use white guilt as a shield to deflect critique of their class position.4

American-born diaspora desis like myself often perform this rhetorical sleight of hand because we are beset with Brahmin guilt and want to minimize Hinduism as a mere expression of Hindu nationalism rather than a lived religion. Ironically, or perhaps tellingly, the diaspora Indians resemble the Brahmin left, a term Thomas Piketty coined to describe the elite left in the West. He was talking about whites, but my American-raised desi peers are prone to a caste guilt almost identical to the professional class’s white guilt. But of course, these two types of guilt are actually about class guilt, for which race and caste serve as proxies.

My parents’ being Brahmins didn’t mean I belonged among the Indians because my parents were still not wealthy professionals. I grew up outside the local Indian community and saw patterns in the behavior of professional-class Indians of all kinds that no white person has the background to see. Class, regional origin, and caste are the primary fault lines among Indians today, though we never talk about the first, exactly as among the rest of the PMC.

Do Indians think I’m Indian?

I’ve taken to polling Indian immigrants on this subject informally, and they universally say diaspora Indians like me are American. They cite not living among the culture and people, as well as our personality inclination toward self-expression and individualism. I don’t view this as an insult; I am, indeed, American, and I’m not ashamed of it.

Hyphenated identities like ‘Indian-American’ and ‘South Asian-American’ are largely artificial constructs born from elite academic institutions, not organic social realities. For AIDs who don’t have a shared American identity, these identities are sustained through performance, especially in college, but collapse under the weight of real-world experience.

The identity formation process for both these groups is distinct, and here I will focus on the process for AIDs. We want to think we’re Indian but American in our personalities and have no connection to the Indian nation-state. And many of us aren’t Hindu or religious at all. So are we Indian in any way other than being vaguely brown in the eyes of mostly white elites?5

I assert that the way you move through the world has far more to do with personality and experiences than with parentage, though culture does play a role. However, the average personalities of the two groups are fundamentally different because of our upbringing and native cultural context.

iii. The collegiate crucible: becoming Indian-American

At the University of Florida, I became Indian-American and South Asian-American.6 Identity formation and the undergraduate experience are intertwined; neither can exist without the other because group identity becomes the basis of one’s social life. If there weren’t student groups based on ethnicity or national origin, it was fraternities and sororities, some of which are also culturally specific.

I had a veritable buffet of identities to choose from in college. And in a campus of fifty thousand people, it’s understandable that adolescents would want to find a group. The Indian grad students also understandably stuck together; we didn’t mix. There was an Indian Student Association for us and a Graduate Indian Students Association for them. I, however, did hang out with them once I stopped trying to fit in with my peers.7 Today, I have a handful of Indian friends from diverse backgrounds with whom I share interests and values. Last night, I shouted lyrics into the night air with all sorts of Desis at Bollywood Retro Night on 6th Street in Austin - we can come together for the love of Indian mass culture.

My group, of course, was AIDs, because I felt like such an outsider otherwise. But even among them, I was often on the outside.8 I thought they were my people, and they were for a while. Those like me who studied the humanities and social sciences are the most devoted to critical social justice ideology.9 I was once in a Facebook group of alt-desis, and it schismed into a mainstream woke and the true believers who thought the rest of us normie leftists were right-wing.

I provide this background because it contextualizes my identity formation period during adolescence as an Indian-American, and why it remains an empty concept for me today as an adult with real-world experience. In my coursework, I focused on Hinduism, India, and other colonized societies. I was a social justice warrior before the term (or Tumblr) existed, and the American academy was my church. Michel Foucault, Frantz Fanon, Gayatri Spivak, and Jacques Derrida loomed large in the liturgy as our saints. But in this, too, I was an outsider among the Indians — they did not study the humanities and looked at me strangely for paying white people to learn about my own culture, a fair question I ask myself today.

Within each cultural, ethnic, or racial category a student could fall into, primarily white, bourgeois university administrators determined the subgroups that qualified. When the concepts of culture, race, national origin, and ancestry are conflated, you get the incoherent identity framework of the elite left. Racial categories are created from national origin and further reinforce the concepts of blackness and whiteness, despite race not being a biological reality.

Looking back, it is amusing that my Indian-American hyphenated identity crystallized because of my particular academic journey and college experience. Had I not gone to college, this identity wouldn’t exist and certainly wouldn’t be the imagined basis of any political action on behalf of other groups. I might never have lost my devotion from childhood.

The categories of ethnicity and race don’t exist in the real world of the working class as they do in the symbolic one of the university because there are no centers for Latin American/Black/Asian life or ‘area studies’. Multiculturalism is a decidedly bourgeois project and isn’t an expression of classical liberalism, as claimed.

These academic categories are closely tied to campus multiculturalism. Academia produced the categories of ‘South Asian’ or ‘Indian,’ and college life rendered India a performance category. For people like me, the Indian-American identity is similarly born by coming of age in Western universities. We have the highest levels of educational attainment of all ‘racial’ groups, making this process invisible.

Finally, becoming Indian was also about literal performance: we had the broadest spectrum of performance art of all the ethnic student groups. Events showcasing various dance forms were just the start; dance teams were our original sororities and frats. And the dance teams had a hierarchy of social cachet; the classical dance team, composed only of women, was the least cool, and of course, I was in that one. We were compelled to combine Bharatanatyam with Indian hip hop (a distinct genre) to keep up with the others.10

There’s a competition circuit for every kind of dance at every level in the US, where desi subcultures thrive and social networks are fomented. Even today, I’m part of a Bollywood dance troupe because it’s a nexus of social life, not because I enjoy it. I’ve studied two forms of classical dance, and in addition to this, I can inform you about Hindustani music theory.

Fundamentally, AIDs judge each other based on their perceived level of ‘desi’, the factors being language, performance art, sexual conservatism (or at least once did), religiosity, and whether one has desi friends. I leaned in when I entered college because I had never had Indian friends.

Meanwhile, AIDs judge IOAs on their perceived level of assimilation into American society. If Indian-origin people have insight on what you all judge my ilk for, I’d love to know.

iv. “Indian” is a classed identity, not ethnic or national

I now operate outside the black/white racial binary in which elite white people have ensnared immigrants and their children, and I don’t consider myself ‘Indian’. Indians from India mock Americans of Indian heritage like me for caring about being Indian at all, and rightly so.

Gayatri Spivak once argued for a ‘strategic essentialism,’ whereby identity categories can be crystallized to support the political projects we see on the left today. We know how that went. Race became crystallized rather than being a mere vehicle for political demands. I was caught up in this process as a youth until my mid-thirties.

I thought I was Indian until I worked with actual Indians as a product manager, which I will explain in the second installment. In the meantime, please leave me with more questions to ponder and tell me what I may not see, primarily directed at actual Indians — I know there is a non-zero number of you reading this. In closing, I want to remind you that I wrote this to make the diaspora a little more legible to outsiders and ourselves, not to critique any individual’s behavior, for I have enough of my own to critique. Finally, neither of the two broad groups I’ve described is superior to the other; I’m describing average tendencies resulting from majoritarian cultural influence. Both groups perform well in corporate America, and I will explain why next week.

If you’re a free subscriber, please consider upgrading. This one took ten hours, and I hold myself to a high standard of rigor and quality. Because of my unique combination of insider/outsider subjectivities, you will find topics and takes here that you won’t find elsewhere.

I say this obvious fact because someone also thought, “But you’re generalizing about an entire culture and should treat people as individuals!”—or nuance trolling.

This is a thing we accuse each other of doing.

The internet taking hold freed me.

By the way, I’m Brahmin but feel zero guilt or pride; guilt is a useless, self-serving emotion.

This isn’t about white people as a race but about elites, who happen to be white.

Identities with distinct purposes.

This was my stoner grad student period.

And how did I know this? A group of seniors was performing a dance at the annual Diwali show that I wasn’t asked to be in, and by the end of college, I was hanging out with other brown outsiders.

However, I still don’t regret my humanistic education. It gives me an edge over my peers in the technical and business-facing role I’m in today. Indians do ourselves zero favors by discouraging our children from studying these subjects. We would benefit immensely from learning about the broader world beyond medicine, law, and computer science.

The social pecking order was bhangra, raas, fusion, garba, and Bharatanatyam.

I am watching Game of Thrones again. The backstory is good to visit relative to human history for everything about human social status being connected to blood lines, with few able to circumvent it with their lack of blueblood or lack of advantageous cultural/ethnic origins.

Conversely, utopian progress as depicted in Gene Roddenberry's Star Trek stories where different alien races lived in merit-based harmony, would seem to be the actual goal. However, today the same cohort of powerful people that claim a progressive movement toward a more perfect utopian existence seem to want to go backwards to the system demonstrated by Game of Thrones.

It would be good in my mind that filtering of group belonging goes to the current home country and honors THAT culture while dropping any conflicting cultural practices of the previous home country.

It was back during Teddy Roosevelt where he outlined the dangers of having "hyphenated Americans". I think this is correct. You are either Indian or American, not Indian-American. Or at least I believe that is the way it should be.

I have noticed a lot of AIDs and IOAs, especially women, are uniquely positioned to play the corporate game.

In the workplace, they can play either the Oppressed Minority Demands More Rights! or the Model Minority, and caste politics provides good practice for both roles and switching back and forth as the situation makes convenient.